There’s a semi-decent chance that if you’re enrolled at a Russell Group university in the UK and study something at least closely related to biology, such as biomedical sciences, chemistry, computer science etc. that you’ve heard mention of the phrase iGEM.

iGEM stands for the International Genetically Engineered Machine, and it’s a competition that runs annually out of Boston, Massachusetts encouraging undergraduate and postgraduate university students to get involved in biotechnology. This area of science has advanced such an incredible distance over a relatively short space of time that it’s vital we prepare the next generation of scientists to understand and further develop the tools we’ll need to use it. It usually takes place over a summer, in between academic years of study.

Team members from all over the world at the 2016 iGEM Giant Jamboree

Specifically iGEM is about synthetic biology, which fundamentally combines the principles of engineering (that being standardised systems with intercompatibility) with the techniques of molecular biology, bacteriology and an enormous array of other disciplines. This aim is realised through the use of custom-designed gene constructs that all have characterised functions, which can be combined together to create new constructs with new functions to solve a particular problem faced by society or develop a new tool.

"...just as the LEGO bricks in Beijing will match the LEGO found in Tennessee, all iGEM BioBricks are compatible no matter where on earth you stand"

Think of something like LEGO, for example. Each type of brick interlocks with virtually any other, the analogue in iGEM being ‘BioBricks’, which are genetic sequences with standardised prefixes and suffixes that allow them to be easily ligated together. Every year teams design more parts, building on the work of previous teams which is stored in the iGEM registry and available to everyone, not just competitors but research scientists all over the world. This is a crucial thing to realise, because just as the LEGO bricks in Beijing will match the LEGO found in Tennessee, all iGEM BioBricks are compatible no matter where on earth you stand.

Teams can vary in size and composition, but an example team might consist of say 10 students at undergraduate level. In my case, we had eight - myself and two further biologists, two biomedical science students and three from computer science. Five of us were in our second year of study, two from first year and one from third year at the time.

Our team assembled outside FabLab, Sunderland where we learned about 3D design

You then have to choose a problem to solve - Jake, one of our computer scientists came up with the idea of taking one of those fundamental aspects of iGEM (standardised systems) and trying to coming up with an electrobiological interface, and then producing free part designs that could be used to make them. The example given was build-your-own electronics kits such as those available from Hot Wires, usually given to children, wherein you make customisable circuits to perform a given task.

Long story short, it didn’t work very well but I’ll take you through the process. We learned how to design our own gene constructs using the SBOL Visual standard, had them synthesised and transform them into bacteria, test our constructs and record experimental data. There’s way too much to cover in this short article but I’ll give you a flavour of the sorts of things we got up to over our summer.

"Long story short, it didn’t work very well"

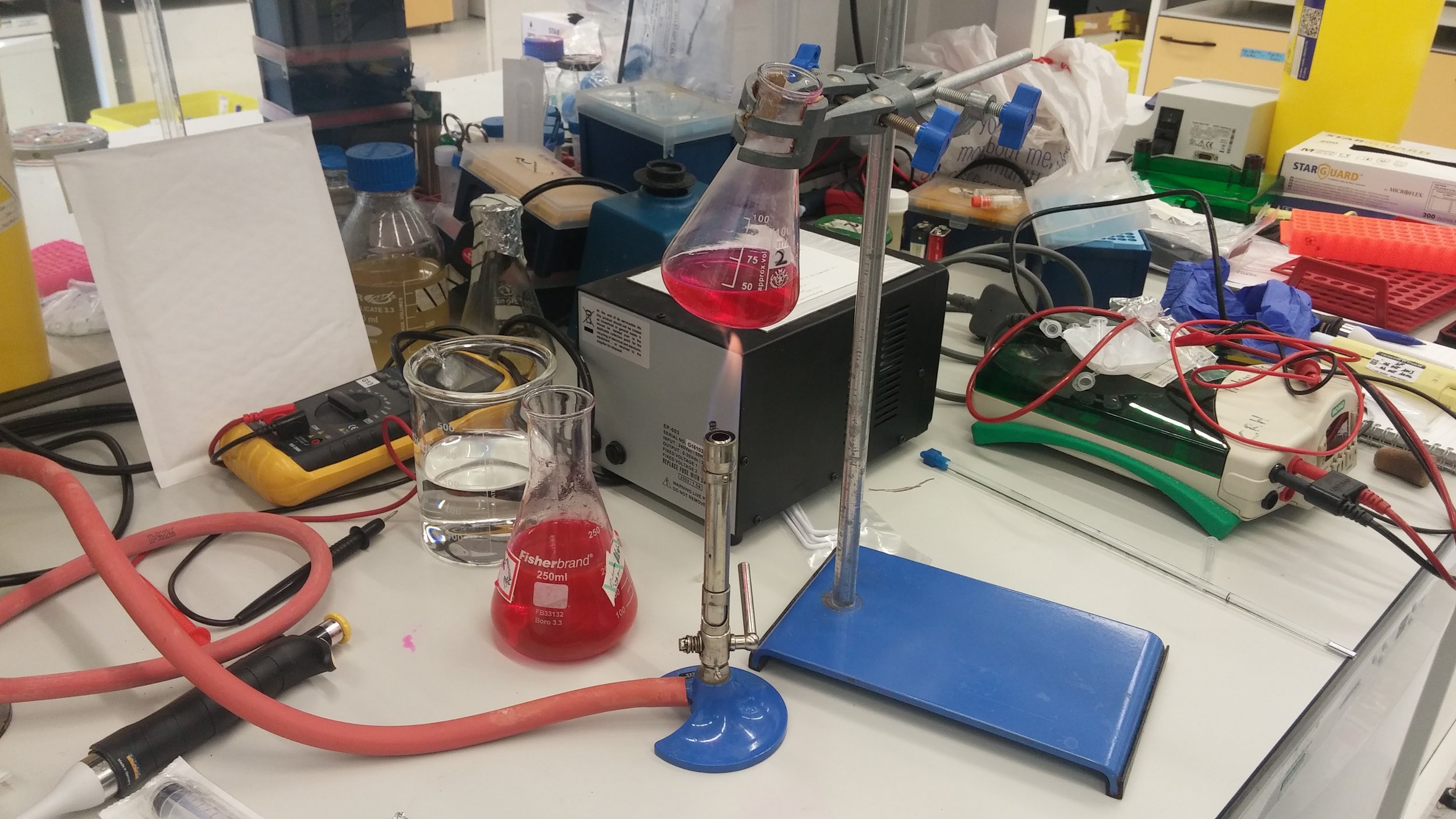

Lab training: You’ll no doubt receive full lab safety and technology briefings, and instructions on how to perform basic procedures alongside whatever specific experiments you wish to carry out. This is immensely valuable because it gives you a hands-on chance to get involved, and learn by success and failure. For example, I learned how to transform and culture cells, then measure growth and GFP fluorescence using industry standard equipment. I’m sure I don’t need to tell you how valuable that would be to a prospective employer or supervisor.

You'll have to come up with novel ways to solve problems

3D Design: One really enjoyable aspect of our project was that because it inherently required physical devices for our electrobiological interface, we had to learn how to manufacture things. To achieve this, we developed partnerships with a local FabLab at the University of Sunderland, a design and fabrication workshop, eventually moving to OpenLab close by at Newcastle University. I learned how to design 3D print models and engineer them for our purposes, soldering everything together and building testing circuits.

Academic Conferences: Of course what you’re doing is fundamentally academic (at least in part) and you need to be able to talk to others about it! Your iGEM work is judged based on a few different aspects, including the novelty of your work and characterisation of your designs, but all of these have to be communicated during your final presentation. To practice for these, you can go to iGEM meetups with other teams over the summer - in our case we attended gatherings in Edinburgh, Paris and Westminster before delivering our final talk in Boston. We designed academic posters and handout materials, and feeling the culmination of everything on that stage was pretty overwhelming.

"You’re not just let loose on the world with big ideas and clumsy hands - you’ll work very closely with academic support"

Support: You’re not just let loose on the world with big ideas and clumsy hands - you’ll work very closely with academic support, in our case a mixture of lab technicians, lecturers and researchers. They’ll be with you every step of the way, training you in the labs, helping you practice your presentations and keeping your organised and on track during the summer. The closeness to these academics that you’ll build up is enormously valuable, because the exposure can’t even be approached during a normal teaching course. I know first-hand that our mentors put in astronomical amounts of effort to get us through the process, and we wanted to work hard to make them proud.

Our team post-speech on the stage in Boston, MA

This doesn’t even approach the enormity of everything we experienced during the summer but if you want to see more, head over to http://2016.igem.org/Team:Newcastle to see our wiki which covers everything in much more depth. If you’re interested in getting involved, be sure to ask your school and don’t hesitate to drop me a line at the contact form if you want to learn more.