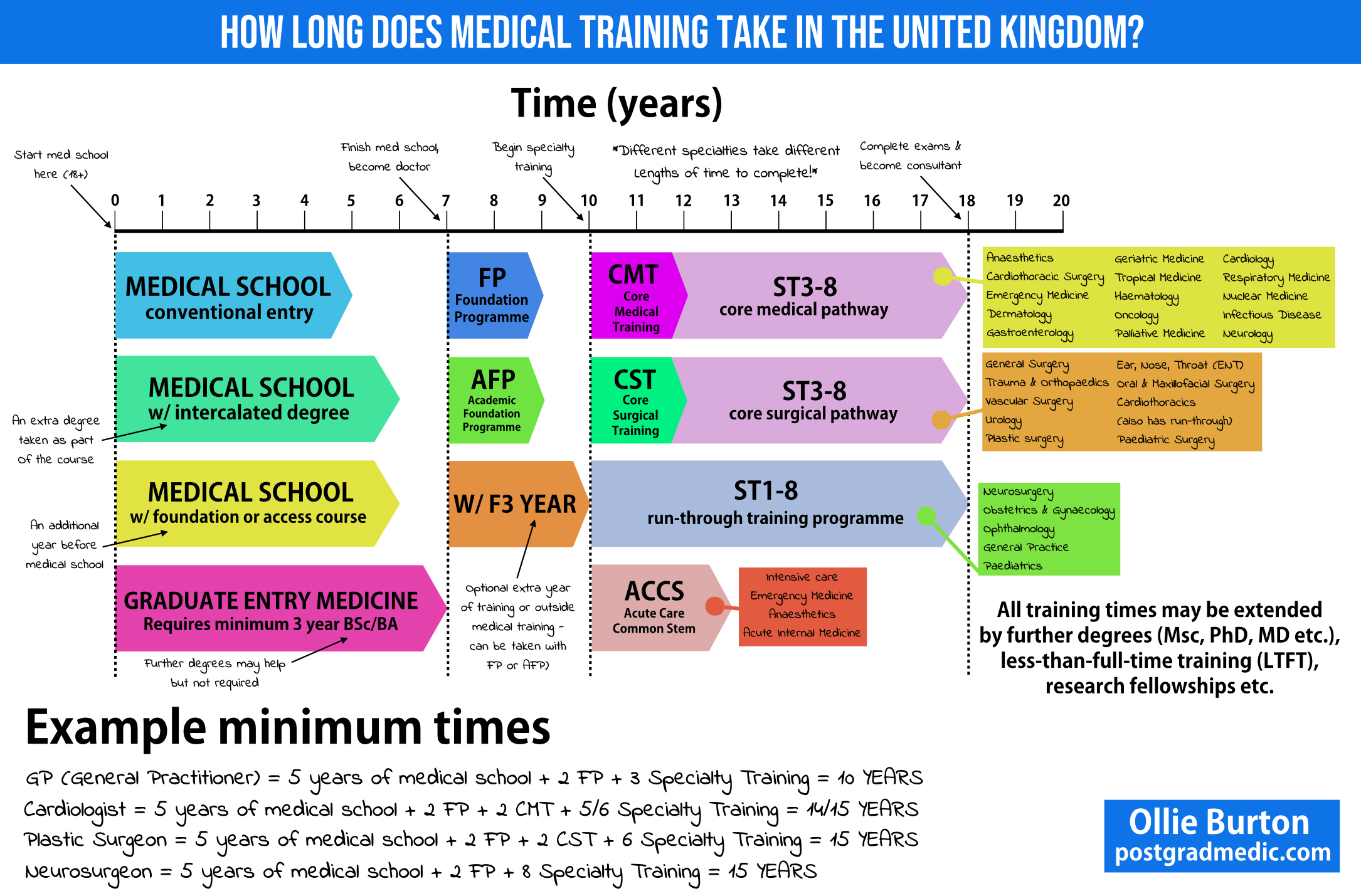

I get asked all the time, especially by friends and family - just how long are you going to be at medical school? It’s something all us medical students need to think about before we start, but even having done a lot of research before I applied, there was still left to learn that I’ve picked up since getting here. I’ve put together an infographic that illustrates the broader guidelines.

Right then, standard entry to medicine. You go when you’re 18 after completing your A levels, entering into first year, and these courses are usually 5 years long. That means you’ll enter at 18 and finish at 23. Some UK schools have an optional or compulsory intercalated degree year for a Bachelor’s or Masters, which would add another year for a total of 6. This would be the same if you completed a Foundation or Access to Medicine course too. Then there’s graduate entry medicine, which requires at the very least an undergraduate degree to complete, which is a 3 year investment. However the tradeoff here is that you essentially get to skip a year of the course due to the content being compressed, which makes it 7 years long.

Congratulations, you’ve finished medical school and passed your final exams. You are now able to call yourself Doctor with some letters after your name such as MBBS or MBChB - they’re all equivalent, don’t worry. This is the point at which you start earning money. You then have to complete 2 years of Foundation Training as a junior doctor - in the first year you have a provisional license to practise medicine, with the full license for unsupervised practice being obtained after that first year and then you complete the second year of training with that license. During each of these years you’ll rotate between various specialties and gain a basic set of core competencies.

You can also apply for the Academic Foundation Programme instead, which takes the same amount of time but gives you some protected research time you can spend working on an academic research project or in an educational setting, for example. Some people also choose to take an extra year out here as F3, either to have a break from training or pursue other projects, teach or maybe to get themselves ready for specialty training.

At this point you then need to decide what specialty you want to do and things get a bit more complex! Let’s start simple and say you want to become a General Practitioner - this is currently the shortest training pathway and takes 3 years after completing foundation training, meaning your total medical school journey, assuming you started at 18 in the conventional pathway is 10 years long.

Let’s say you want to be a cardiologist - you’ll need to spend another two years in Core Medical Training, CT1 and CT2, which almost all medical doctors will do. After that, you then apply to go into specialty training specific to cardiology and enter at the ST3 level, or Specialty Training 3, your 3rd year after foundation. You then stay on this programme and go through four more years to ST7, with the option of a final ST8 year to subspecialise and then become a full, bona fide consultant. While you’re in specialty training you are known as a specialty registrar, which is still technically a junior doctor.

Let’s now give a surgical example - you now want to be a orthopedic surgeon. Similar to medical programmes, you need 2 years of core surgical training, CST1 and CST2, which almost all surgeons will do. After that it’s 6 years of specialty training, agains starting at ST3 and ending at ST8 as a consultant surgeon. The other major pathway after foundation training is run-through specialty training programmes. This means that instead of having to do core training and learning the basics that overlap with other specialties, you focus on the end goal right from the start and only do training relevant to that job. A good example is neurosurgery, where instead of CST1 and 2, you begin right away at ST1 and go right through to ST8. There are advantages and disadvantages to this - there is only competitive step, entry to ST1, so once you’ve got your foot in the door you’re sorted until the end. Obviously if you change your mind it’s a lot more difficult to change direction because you have not done the core training which would allow you to enter a different specialty later.

The last pathway we’re going to discuss here is ACCS - the acute care common stem training programme. This pathway focuses as the name suggests on four acute care parent specialties - intensive care, emergency medicine, acute internal medicine and anaesthetics. This pathway takes 3 years to complete, and allows you to undertake higher training in those parent specialties. Anaesthetics for example also has its own core medical training programme, so be sure to look more at CMT and ACCS if that’s something you’re interested in.

So that’s a very quick overview of higher medical training through junior and senior ranks. We said earlier for a GP you’re looking at 10 years minimum investment. For most others it’s another 5 years on top of that - you could go in at 18 and be 33 as a consultant. Of course that assumes you don’t do anything else, like Masters Degrees, PhDs/MDs, research fellowships, teaching placements etc which would extend it further.